In my 30-plus years of conducting psychotherapy with clients across all age ranges, I’ve not worked with a patient whose life ended via suicide, knock on wood. I have, however, had several clients with a history of suicidal ideation coupled with attempts, prior to coming to me – attempts, which in some instances, continued during our time together before eventually remitting.

Suicidal clients can evoke disquieting feelings, trepidation and a sense of uneasiness that can prompt clinicians to feel charged with the rather unenviable task of forecasting and staving off a self-induced death. What can you do – beyond medication – to help your patients who have suicidal ideation, tendencies and attempts? There are several strategies that can be employed, here are a few:

Keep them connected

Don’t lose touch with them. Suicidal patients are notorious for dropping out of treatment. Weak or non-existent support systems, a lack of structure, poor living conditions, substance abuse and importantly, impulsivity, all contribute to high dropout rates. Address possible obstacles to continuing early on when discussing treatment parameters. Ask: “how can I best get in touch with you if you miss an appointment without notifying me?” Conduct missed sessions by phone, if possible.

Convey Hope

Even when a patient’s struggles seem unconquerable, there’s still a reason to hope. Best to avoid using expressions such as “hope springs eternal,” which can come off a bit Pollyannaish and invalidating. Instead, just reinforce the practical value of hope, which invites approaching problems with optimism.

Safety

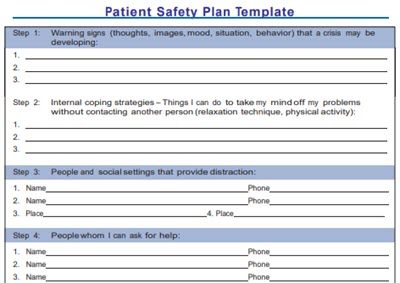

It is incumbent on mental health professionals working with suicidal patients to understand that they aren’t apt to be thinking clearly and rationally when a crisis appears. So, written reminders that address a safety plan are very important. Such a plan should include: phone numbers of support people; numbers for 24-hour emergency health centers (and how you can best be contacted, if applicable); and a suicide hotline. A quick web search will yield downloadable safety plans which can be distributed to patients.

It is incumbent on mental health professionals working with suicidal patients to understand that they aren’t apt to be thinking clearly and rationally when a crisis appears. So, written reminders that address a safety plan are very important. Such a plan should include: phone numbers of support people; numbers for 24-hour emergency health centers (and how you can best be contacted, if applicable); and a suicide hotline. A quick web search will yield downloadable safety plans which can be distributed to patients.

Assessment

It is imperative to evaluate suicide risk collaboratively, soliciting the client’s input regarding problem solving and risk reduction. Approach the assessment with the mindset of placing a foot in the client’s world. When patients feel understood and believe you have their best interest in mind, trust grows, along with their commitment to treatment, serving as a counterbalance to suicidal impulses and tendencies.

The distress meter

Most suicidal impulses are brief, waning after minutes or hours. Very few of such tendencies continue beyond a full day. Cognition becomes clouded when in the throes of a suicidal crisis, so developing distress tolerance skills can help patients outlast bouts of emotional pain. Simple is best for all of us – but particularly for suicidal patients, obviously. Easy to employ is also important: any type of deep breathing; mindfulness exercises; music; a soothing bath; loving on a pet. Distractions via word games or puzzles can lower the distress quotient quickly as they require an immediate change in focus. (Apps: Stress Free; Breathe2Relax).

Coping tools

Things happen quite quickly during a suicidal crisis – thoughts and actions can be impulsive, extreme and even reckless. I’ve long embraced the use of written materials that troubled clients can access quickly, on the spot – in this case – coping cards. On the front of the card is a statement mimicking how the client is feeling in the moment, “my situation is hopeless and will not get better”; on the flip side is a rational, sensible, adaptive response, “this is nothing new for me, I’ve made it through situations that seemed hopeless before.” Have them write up these cards when thinking clearly.

Hope Chest

This tool consolidates everything discussed so far – all in one place. It’s an actual box that patients make to store all of what they’ve accumulated to help them through a crisis. The names and contact numbers of support people, coping cards and tools, distress-related exercises, all go in the box. Also in the box: a list of positives for why life is precious and worth living, together with visual, heartfelt reminders such as family photos, past achievements – all there to challenge and counter thoughts and feelings of helplessness. (App: Virtual Hope Box).

A final point: All of the above transposes the focus toward what’s within the patient’s (and counselor/therapist’s) grasp and control, fostering empowerment all around. So instead of utilizing safety contracts to deter them from what they shouldn’t do, the approaches discussed here emphasize what they can do when a crisis emerges.

Attribution Statement:

Joe Wegmann is a licensed pharmacist & clinical social worker has presented psychopharmacology seminars to over 10,000 healthcare professionals in 46 states, and maintains an active psychotherapy practice specializing in the treatment of depression and anxiety. He is the author of Psychopharmacology: Straight Talk on Mental Health Medications, published by PESI, Inc.

To learn more about Joe’s programs, visit the Programs section of this website or contribute a question for Joe to answer in a future article: joe@thepharmatherapist.com.